by Julie Krejčí

Last week we looked at the origins of decolonization and its connection to art. Today I want to delve into art history, as a means of showing the past in its full complexity. The academic writing regarding decolonizing art history is somewhat slim, with the exception of the article “Decolonizing Art History” published in January 2020 which involved dozens of interviews with persons from all corners of the art world. I draw from this article and look for patterns and similarities between the four questions asked by Catherine Grand and Dorothy Price regarding the process of decolonizing and the distinct ways of implementing change in the art world. I have thus recognized two major aspects of changing art history for the better.

Firstly, decolonizing the curriculum that is being taught. The history of art is created through the lens of the western canon, which is inherently rooted in colonial history and represented through the English language. A structural intervention of art history is necessary along with the contextualization of euro-colonial art as a product of an empire and its immense impact. Victorian Jamaica (2018) – a study of Jamaican culture under colonialism – serves as an example, where its creators suggest that understanding Jamaica under colonialism is central to understanding British culture in the age of empire. However, I would go even a step further to argue that the objective should be to place the art of cultures that were colonized at the heart of discussions in order to decentralize the western narrative.

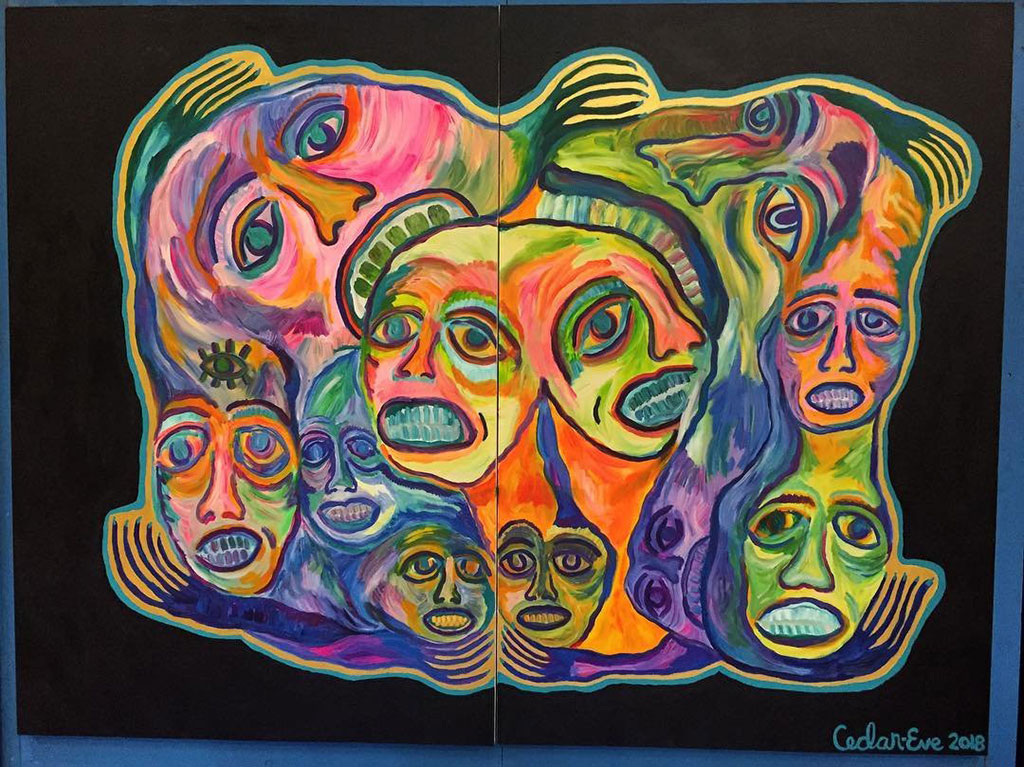

Second, is the question of how the world that is being produced feels to all of those who are living in it. Perspectives that are once imperialist and hegemonic must transform into transnational narratives, diversifying the voices and holding space for marginalized and underrepresented groups to share their part of history through art. The focus should shift to non-western tradition and indigenous art as a way of completing and rewriting history so that it feels accessible and whole to all. As mentioned in my previous article, the removal of the symbols of oppression play a vital role in changing the way history is seen through everyday objects we encounter moving through this world. Thus, removing statues such as that of Cecil Rhodes or John C. Calhoun is an effective way of showing marginalized communities that the oppressors of their generational past are not to be celebrated but rather removed in order to create space for their history to be shared.

Apologists argue that the discipline of art history is rooted in tradition and discipline, enabling ignorance and colonial thinking in the art world to fester. For so long art history has omitted artists from colonized territories and labeled them as unimportant, but the sole fact that they exist despite such efforts to forget them shows how necessary they are for the re-writing of history to be complete.

Next week we will look at art institutions and how they can do better at decolonizing their spaces. Whether it be broadening the canon or erasing the distinction between “fine art”, “decorative” and “ethnographic” Museums, we shall explore what experts and institutions themselves have to say about decolonization.