by Julie Krejčí

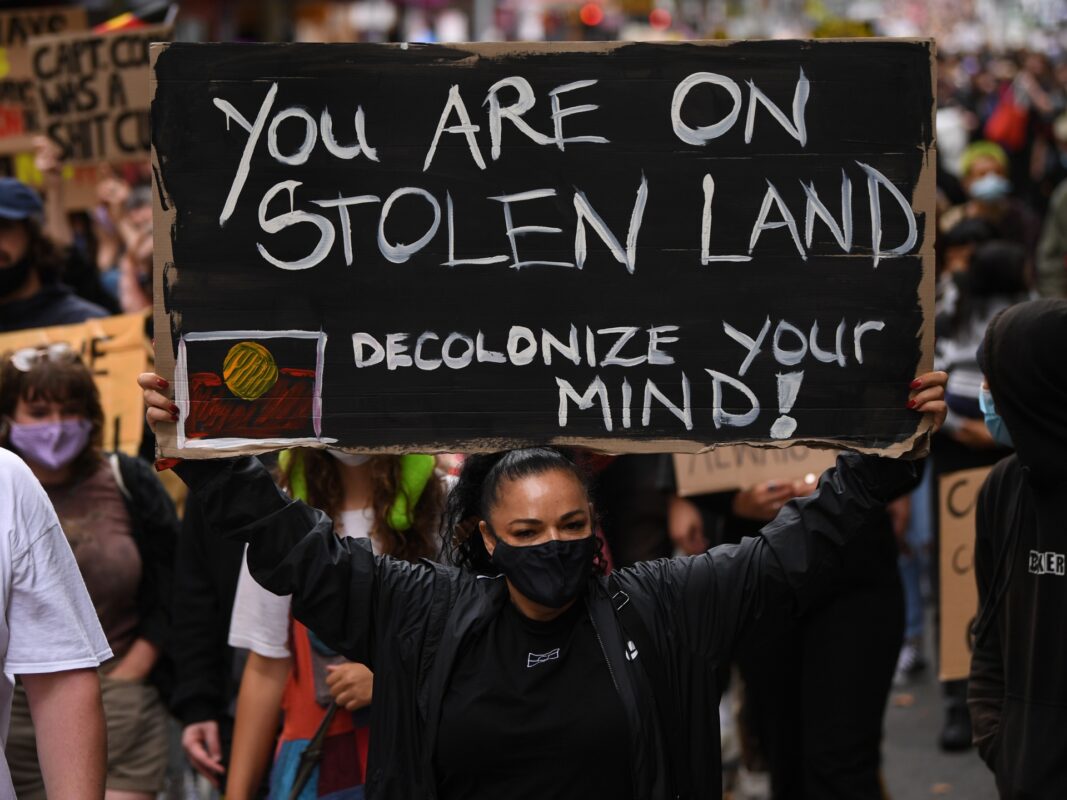

The Western world; sparkles from the outside, while rotting rapidly on the inside. The very strategies that brought it to where it now has only stolen, destroyed and appropriated cultures all around the world. Modern imperialism and colonialism have been part of European history ever since the 15th century. One might assume that those are strategies of the past, yet their impact has been woven into all areas of our daily lives. The process of healing and repairing this gruesome part of history has only just begun.

One of the methods of reparation of history is de-colonization, originally used to describe the process of colonial powers relocating institutional and legal control over their territories and dependencies to indigenously based nation-sates” (Duara, 2004, p.2). However, in recent years, it has become a part of the rhetoric regarding the improvement of the art world – “an approach to the past and an attitude towards the modern” (Grant, Price, 2020). The art world, especially art history has been preserved by the traditional, colonial mindset, keeping the discourses that challenge and enrich it away from the original premise so as to preserve it. This notion must be challenged if any real change is to happen.

Thus, for the upcoming three weeks, I have decided to write a short series discussing the de-colonization of the art world, focusing not only on the importance of decolonizing art history but also its institutions. In today’s article, I give a brief history of decolonization as a movement in order to dive deeper into the analysis of decolonizing art history and art institutions in the upcoming few weeks.

When did the process of decolonization begin? And where? These questions are vital, yet nearly impossible to answer. Western countries, such as the UK, Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain among others have managed to colonize more than 80% of the world in-between 1949 and 1914 (Stoller-Conrad, 2011). Hence there has been only a few historical studies on decolonization, as the topic is so extensive it is nearly impossible to cover all ground. Not only can it not be linked to a single event, but it is extremely varied, encompassing several places at various times all around the world. Even with a simple focus on its relationship to the art world, there is not enough room for this article to categorically include all territories that have been colonized throughout the years. The relationship between colonization and art is incredibly tangled and intertwined; from the appropriation of styles of colonized territories to the exclusion of minorities in today’s collections.

Nonetheless, I will attempt to contextualize the slow process of de-colonization of the art world as tangibly as possible. Upon extensive research, I have decided to focus on a singular event, merely because it serves as a contemporary example of decolonization and provides the space for the exploration of its contextualization. I hope that it will serve as a lens for looking at how decolonization can be done and the events necessary for the movement to gain momentum.

Cape Town, March 9th, 2015: students of the University of Cape Town gather in protest to signal their condemnation of the institutional racism in the university. Their campaign manifests in the removal of the statue of Cecil Rhodes – white supremacists and imperialists, towering over the university, a symbol of violence and divide. Coming from young artists, scholars, curators, and students demanding institutions from which they feel excluded to listen; The message is not new, but the sense of urgency is. A buildup of decades, from social movements of the 1960s that were influenced by the history of anti-colonial political and cultural activism to the hangover of Apartheid. It is the significance of the statue that has made the movement so memorable, that has led to the removal of colonial symbols all around the world. Whether we like to admit it or not – art is symbolism and #Rhodesmustfall serves as a powerful visualization of the merging of art with racist foundations of European colonialism and imperialism. They have meshed together so well, they have become nearly identical, art holding the power to speak for the silent actions of our governments. By removing the statues that are meant to celebrate and memorialize the past so violently, activists are able to show the world that inclusion must happen on a higher level. That is the message of decolonization – addressing the past, allowing it to be challenged and rewritten through narratives that have been long suppressed.

Next time we look into the specifics of decolonizing art history, which aims to encompass multiple modernities. Modernities that have been repressed in the past, allow art history to become a space of inclusion, appreciation, and representation. We will discuss the practices of decolonizing art history and the steps necessary to get us to an accurate narration of the past next week.

Sources