by Sofia Reyes

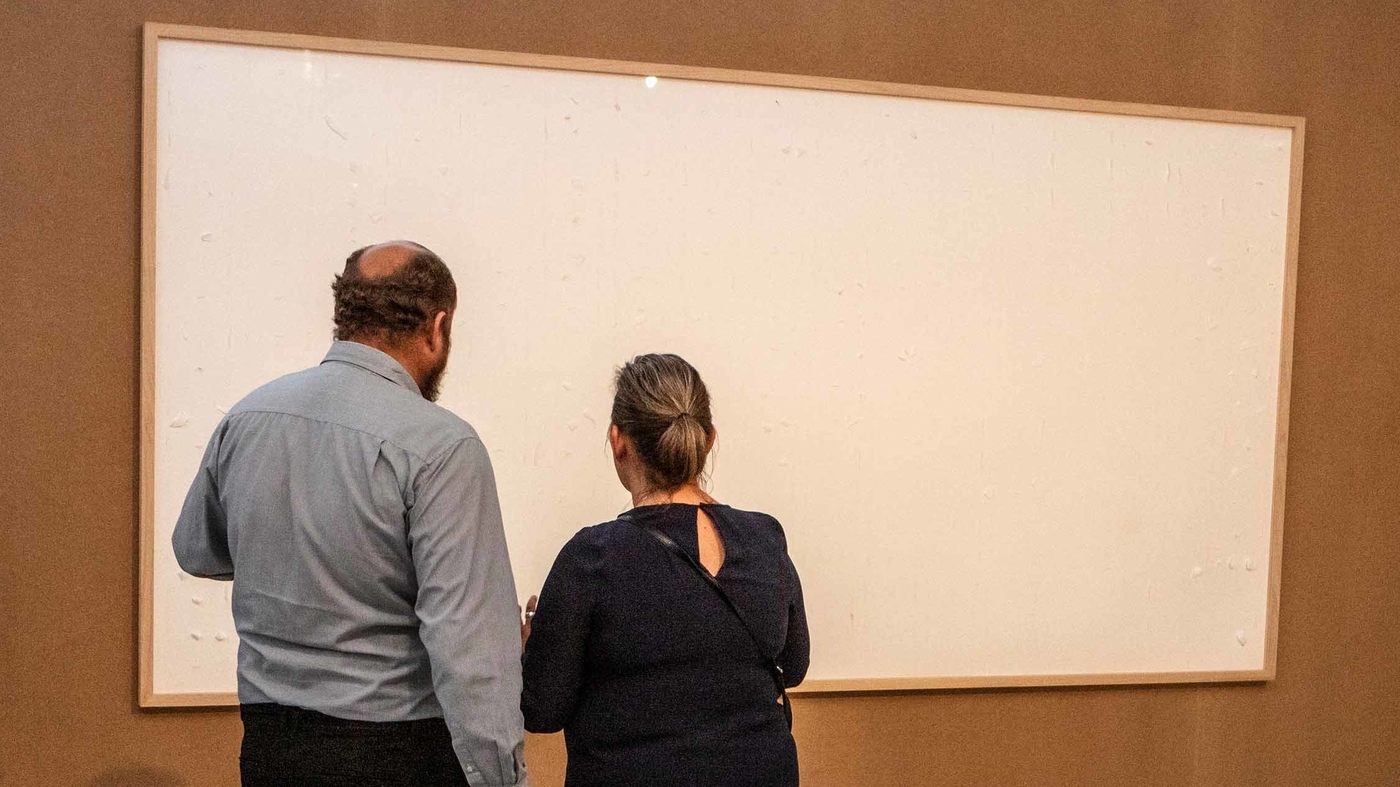

In 2021, the Kunsten Museum of Modern Art Aalborg partnered with Danish artist Jens Haaning, known for exposing social injustice in his art. He was given 532,549 DKK (more than 70,000 EUR) to create two blank canvases with those same banknotes inserted into the artwork, representing the average wage in Denmark and Austria. But here comes the twist: Jens delivered two blank canvases and titled them “Take the Money and Run.” The museum exhibited these blank works, but demanded the artist to return the money on the grounds that he was entitled to it. Jens objected to the return and the Kunsten Museum took the case to the Danish courts.

In September 2023, the court ruled in favor of the museum. Jens has to return the money, but not the full amount because he is due 40,000 DKK in fees. The court focused on what was previously stipulated in the contract, which states that the money was to be returned when the exhibition ends and any modification requires express consent from both parties.

Jens, who disagreed with the court, voiced his opposition and even incited people to act in the same way: “I encourage other people who have working conditions as miserable as mine to do the same. If they’re sitting in some shitty job and not getting paid, and are actually being asked to pay money to go to work, then grab what you can and beat it.” The artist believes that his artwork was to keep the money; his intention was to protest against his own working conditions.

Haaning’s conceptual brilliance lay in the deliberate omission—the absence of the expected representation, challenging norms and serving as a bold commentary on his working conditions. However, this case underscores the crucial role that contractual agreements play in shaping the boundaries of artistic endeavors, reminding us that even the most avant-garde forms of expression are tethered to the pragmatic world of legal agreements.