By Lisa Gordon

Historically, feminist artistic practice has dealt largely with the female form and its representation – often in relation to the male gaze. Artists such as Judy Chicago and Louise Bourgeois regularly used the body as a medium to highlight the positions of women in society. As Lucy Lippard said: ‘’When women use their own bodies in their artwork, they are using their selves; a significant psychological factor converts these bodies or faces from object to subject. Works such as theirs asked society to question its social and political norms.’’1

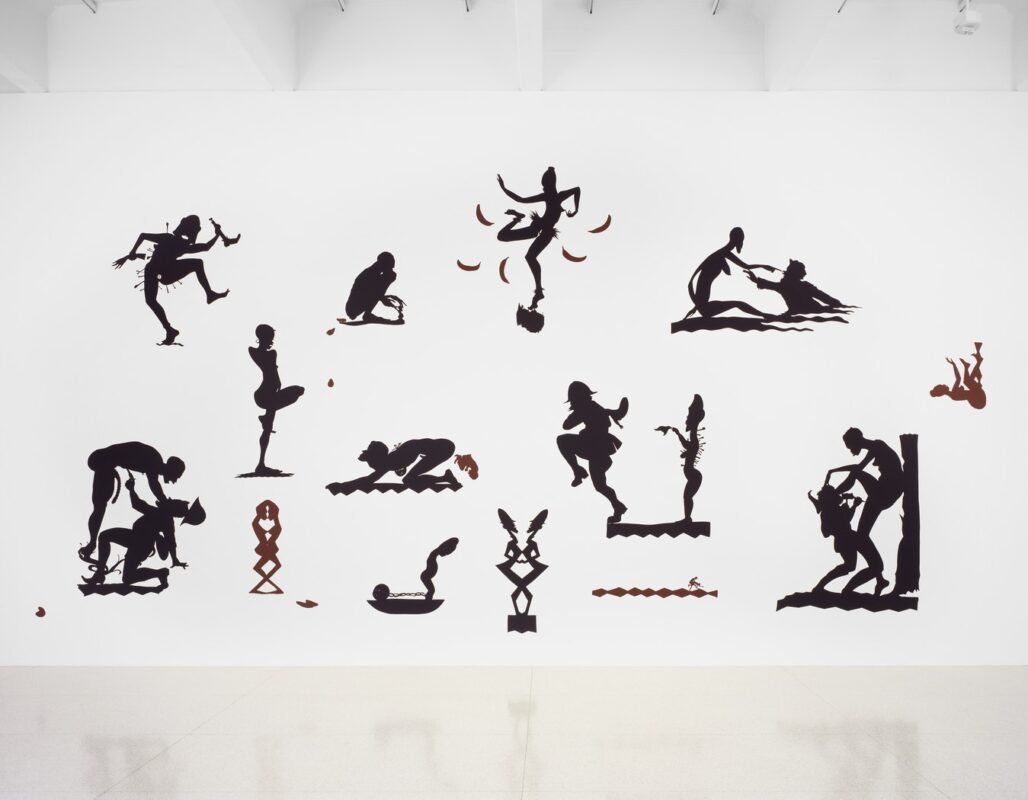

New Time: Art and Feminisms is currently on show at BAMPFA, California and features the work of more than 150 works by seventy-seven artists and collectives. The exhibition is organized around eight themes: hysteria; the gaze; revisiting historical subjects through a feminist lens; the fragmented female body; gender fluidity; labor, domesticity, and activism; female anger; and feminist utopias. The exhibition explores recent feminist practices in contemporary art in a way that highlights the complex interactions of gender, culture, age, and privilege – to name but a few issues. It aims to demonstrate that feminism is diverse, and therefore cannot be reduced to a single subject.

Contextualizing these histories and recent feminist artistic practices in the cultural sphere is of course important, but what’s going on behind the scenes? “We have a bias in not respecting and not being interested in a feminine way of seeing the world,’’ says Micol Hebron, an L.A.–based artist, performer, curator and gallery founder. “You are more likely to make money selling or reselling art by a man than a woman. And it’s not because women make work that’s less good. It’s because we’ve made capitalism a patriarchal system.’’2 Feminist-based art practices and works made by women are still viewed by many as ‘other’ or ‘niche’ and not representative of societal issues which affect all of us. This is one of the reasons why it is not only important to normalize representations of women from all backgrounds but to diversify who is representing them. The art world needs to think more about who its stakeholders are: who curates in museums and galleries, who deals with the pricing and selling of art and who gets to critique it. Organizations such as ODBK argue that these processes should be carried out by a diverse cross-section of genders, nationalities, social status and identities, and only then can the playing field really be leveled. Let us continue to represent the broad spectrum of our society’s feminisms but let us also unmask and reshape the dominant structures which are still at the heart of the industry

1. https://www.theartstory.org/movement/feminist-art/history-and-concepts/, accessed on 29.08.2021

2. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/art-world-bias-by-the-numbers-94829, accessed on 30.08.2021